In the interim time between my school breaking up for summer and a local comprehensive breaking up for summer, I spent several days in the comprehensive to help out. Part of that effort was explaining the role of CPACs in the assessment of A-level science practicals (see previous post). A key aspect of my presentation was common issues faced with each CPAC and how to overcome them. Here are my thoughts.

CPAC 1

Can your pupils follow written instructions? The word “written” is a keyword, but, otherwise, it is fairly self-explanatory. Many schools and colleges find this to be the easiest CPAC to pass.

Common issues with this CPAC are:

- Teachers with large class sizes only assess half the class in pair-work, which puts pressure on competency development if only the 12 required practicals are delivered. The point here is that you are assessing independent work. If you can afford enough equipment (and have sufficient time) for each pupil to do the experiment themselves and for you to observe them to the correct standard, great. Similarly, if you have enough time in a lesson with pair-work to pull the experiment apart and get the second pupil to rebuild it, great. Otherwise, you may face this issue. The solution is good planning to ensure that the CPAC is covered in (probably) six of the practicals – that is so each pupil in a pair can cover it three times, allowing one failure and two successes to demonstrate “routine” behaviour

- Assuming the CPAC is met based on the quality of data. I am sure we have all at least felt this at one time or another – “the data is good so the pupil must have done the experiment right.” Unfortunately, such an approach is insufficient and the onus is on the teacher to go on walkabout and observe everyone to the right standard during the CPAC element

- Providing written instructions that are deemed “too easy.” I have struggled with this in the past and I decided that it is most easily overcome if one’s instructions are at the same level of difficulty or harder than the exam board. This is really easy to achieve if you are running one of the required practicals from the exam board, because you can download their instructions as a starting point and either leave them as-is or delete part of them

- Repeating a practical purely for the assessor’s benefit. This does happen but there is absolutely no need. Expect to be reprimanded by the assessor if a pupil tells him/her “it worked when we did this experiment last week”

- Teacher demonstration delivered in same lesson as practical endorsement. A recurring theme with all of the CPACs is how do you know that the pupil is showing independence if you have demonstrated the correct behaviour in the same lesson? They may simply be following what you just showed them. Giving a demonstration in the previous lesson, or directing the pupils to a video of a demonstration as homework immediately prior to the lesson are both okay, so alternatives exist should you want to use them

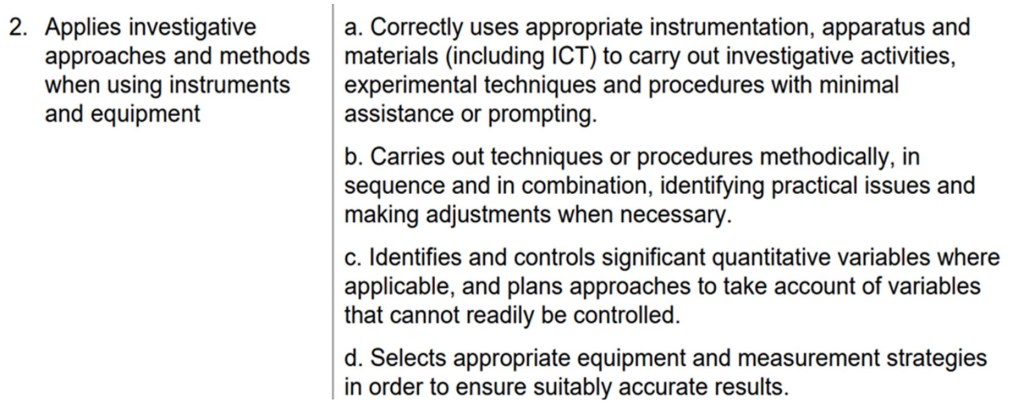

CPAC 2

This CPAC is the meat and potatoes of actually using experimental equipment. Each exam board has a list of apparatus and techniques required but they seem to be fairly consistent. Here is the AQA’s list:

Common issues with this CPAC include:

- Not endorsing all four subsections. Some exam boards require you to hit all four separately, others do not. I find the easiest approach is to ensure that your two-year CPAC planning for the current cohort has built-in the target of hitting all subsections

- Lack of choice of resources. How can a pupil make adjustments (2b) if your school or college only has equipment to do it one way? With a bit of imagination, you can successfully pass this. For example, changing the resolution dial on a multimeter is an adjustment. Similarly, you could, in principle, give a set of instructions with two of the elements in the wrong order or a key point omitted such that the pupil has to adjust the instructions to make it work. An example of this could be to omit the instruction to turn off the power supply in between measurements of resistance in the practical to find the resistivity of constantan. Thermal dissipation will impair the data unless the pupils adjust the instructions accordingly

- Teachers “stepping in” too soon. I find the best thing to do is walk around and observe, only stepping in when asked by a pupil and, even then, failing the pupil if they ask too many questions (which links heavily to CPAC 1). An exception for me is in certain practicals where I want to check that the apparatus is built correctly before the pupils start taking data. This is usually in those practicals with a stronger requirement on health and safety

- Lack of technician support to model a range of techniques

- Lack of understanding of glossary terms (e.g., “accurate”). Ideally, you should be using correct terminology in every lesson. If not, start doing so

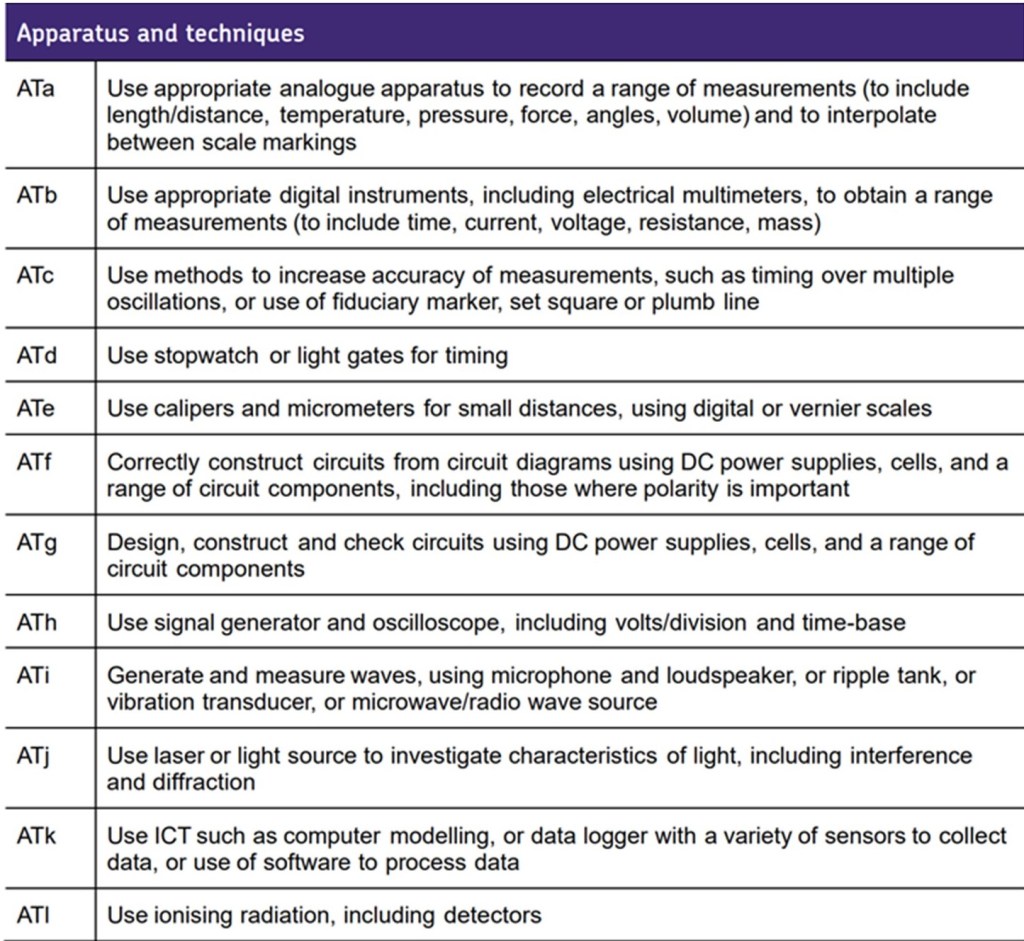

CPAC 3

CPAC 3 is all about risks and hazards. 3a is the more theoretical side, whilst 3b is about putting that into practice.

Common issues with this CPAC include:

- Pupils not having heard of CLEAPSS or Hazcards. I think these two keywords should be seen as a minimum expectation. In my school, we put out the hazcards for every experiment from yr 7 through to yr 13, so the pupils are embedded within a culture of risk assessment. It works

- Using a “nothing went wrong” approach. This is very similar to CPAC 1, issue 2. With hindsight, no-one got injured so it was clearly safe! It works as a message until it goes wrong, but then it is too late for the pupil and possibly the teacher!

- Using a bare-bones “tie hair back,” “put bags under stools” approach. This falls under the definition of box-ticking rather than an authentic attempt to learn experimental skills. Ultimately, we are in big school now and risk assessments should be complete

- Open questioning of class to mind map hazards, risks, and mitigations immediately prior to the assessment. See CPAC 1, issue 5. As a general rule, do not group think or demonstrate answers to a CPAC that you are assessing in the same lesson as the assessment

CPAC 4

There are several key terms included in the wording of the subsections here. Unsurprisingly, a major issue is regarding the definitions of these key terms. I list the common issues with this CPAC below but, from spending time in various schools, I can tell you that they all have the same answer. Ultimately, those schools and colleges that see the “foundations of physics” module (where you teach error analysis, etc) as something to get through have more of an issue than those schools and colleges that interweave discussions and analyses of errors throughout every lesson of the course. I encourage you all to embed!

- Lack of understanding of glossary terms (e.g., “accurate”)

- Not understanding errors associated with key apparatus, such that insufficient data was recorded for uncertainty calculations

- Not recording data on collection (e.g., writing up a neat data table in the lab book after the event)

- Not understanding the difference between decimal places and significant figures

- Lack of repeats when expected

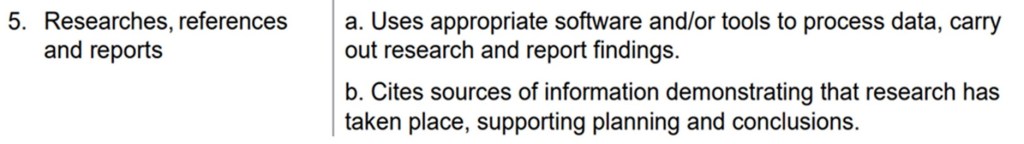

CPAC 5

For 5a, use of a calculator is sufficient (I kid you not!) but why stop there? Data recorders (e.g., the Vernier suite, Labdisk, light gates, etc) should be appearing in the required practicals often enough that the pupils easily pass this CPAC many times over. Similarly, use of, e.g., Microsoft Excel or Google Sheets to plot data is a great addition to your pupils’ toolboxes. I like my pupils to photograph some elements of the practicals on their devices as part of their record, which is another example of a pass.

Common issues with this CPAC include:

- Whilst a “full” report is not required, sufficient detail to help a pupil answer a related exam question is required. This essentially means that, for those practicals that you have selected to test this CPAC, the pupils’ notes should be complete and coherent

- Insufficient or incorrect referencing. How many is enough? It depends on the practical. If I am asking my pupils to develop a method to measure something, I am probably looking for five references of ideas. If I am asking my pupils to find a known value of something, I am probably looking for one reference (not Google or Wikipedia!)

- Not understanding what conclusions are. Yet again, emphasis on knowing the keywords/glossary. It is your job as a teacher to model this language as often as practicable

Summary

In summary, a variety of issues arise with the CPACs in A-level Physics practicals which can be loosely classified as being the pupil’s responsibility or the teacher’s responsibility. As teachers, we must model and embed as much as possible to help our pupils overcome the issues and we must be fair and vigilant when assessing.

Hopefully, I have given sufficient guidance above for you to make headway with the practical endorsements with confidence. Success!

Leave a comment