In my experience, two things hold true with the electricity topic. Firstly, no matter when I teach it (which is currently in years 8, 10, and 12), the pupils find it the hardest topic in the course. Secondly, no matter how many times I have taught it, it remains my favourite topic to teach.

Why do the pupils find it so hard? The answer has several facets but, ultimately, it is because it is a very complex topic! To support this, we are talking about particles that they cannot see and forces that they cannot feel – they have no baseline to work from. On top of this, most of the topic is too high level for the teacher to go into, so a lot of what the pupils are exposed to is phenomenological – they cannot really dig deeper with what they have been given. Also, experiments in Electricity can be a bit hit and miss. Years of misuse of equipment and returning of blown bulbs to the box means that you have to be persistent and give things a bit of a jiggle… they are not always the most convincing practicals in the world. When I ask pupils how they cope with the topic, the most frequent response is that it is just something to get through and they will cram it the night before the exam, reinforcing the fact they feel lost.

Why is it my favourite topic to teach? There are many ways to teach it; it is one of those quintessential topics where you can literally see the transition in your pupils’ eyes from vacant abandon to realisation (if it comes!); it is beautifully logical and links nicely to other parts of the specification (e.g., energy stores and transfers, energy resources, and electromagnetism).

In terms of teaching Electricity, one of the most valuable things I have learned through experience is that the less I talk about cables, resistors, cells, etc, the more my pupils understand and the higher they score in assessments. In fact, recently I have been teaching the topic at GCSE over six double periods and I am now able to avoid saying anything even remotely electrical for three of those. How is this possible, I hear you ask. Welcome to the world of analogous circuit models!

What are analogous circuit models?

Analogous circuit models are easy comparisons to electrical circuits. The word “easy” is essential in this definition because if the model is harder than the real deal, it defeats the purpose of explaining relevant phenomena for less cognitive load. The word “comparison” can be extended to mean usefully comparable to a specific aspect of a real circuit that we care about.

Several circuit analogies exist – we are not reinventing the wheel here – and I encourage you to search online to get a feel for them. Common ones include:

- The rope model

- The water pipe model

- The bandsaw model

- The train model

To show the power of circuit analogies I will use a common issue amongst pupil cohorts: The difficulty they face with the concept of Kirchoff’s first law (and I mean at a really basic level of “what goes in must come out” rather than something higher level about conservation of charge). Talking about Kirchoff’s first law, drawing pictures of circuits, and writing equations, all help lose the pupils, driving them away from Physics forevermore. However, if you show them a picture of a water pipe that splits into two new pipes, you tell them that the original pipe lets 1 litre of water through it per second, and one of the two secondary pipes carries away 0.7 litres per second, every pupil in the class will instantly agree that the other secondary pipe is carrying away 0.3 litres per second. By analogy to a water pipe, they have just explained Kirchoff’s first law with ease! What made the difference? They have no concept of what an electron is but water is easy(ish).

Once we have chosen an analogy that we like the look of, we can then poke and prod it to see where it breaks down. With the water pipe model above, trust me that it rapidly becomes complex as pupils struggle with the concepts of water pumps, radiators, and flow rate as a function of pipe diameter. The analogy quickly fails on its first requirement to be easy. However, Kirchoff’s first law is now learnt and the pupils have a feel for the game that is unfolding!

At this point in the lesson I would normally split the pupils into groups and get each group to research one of the models listed above. As a bare minimum, I would like the pupils to try to use their selected model to:

- Explain voltage

- Explain current

- Explain resistance

- Demonstrate a series circuit with two identical resistors

- Demonstrate a parallel circuit with two identical resistors (one per branch)

The groups would then need to give a short (one slide) presentation on their analogous model to the class, including where it breaks down, and, at the end, the class can decide which one is their favourite.

In the rest of this post I am going to use the shopping model to try to explain several electric circuit phenomena. The shopping model was introduced to me in my previous school and I instantly embraced it.

The shopping model

The basics

The basic premise of the shopping model is that you collect money from home, walk into town, spend the money in the shops, then walk home. Easy! To get buy-in from the pupils, you can have a quick discussion about how much money is appropriate (know your audience – some may have none) and what their favourite shops are (cue the silence in case of embarrassment).

How to switch between the analogy and a real circuit?

- The electromotive force is given by the amount of money you collect from home

- The potential difference is given by the amount of money you spend in a shop

- The current is given by how many times per day you make the journey

A series circuit with one resistor

Here is a specific example where you collect £5 from home, walk to town where there is a single shop, spend the £5, and return home to repeat the exercise tomorrow. The fact that you spend the £5 you collected from home is Kirchoff’s second law. The fact that I will see you anywhere on the road once per day is Kirchoff’s first law. Easy!

The above is clear and concise with quite a nice and logical storyline to it. At face value, the analogy seems to be working.

Note that I have made no mention of resistance at this point. Ohm’s law becomes tricky once you realise that the unit of resistance in the analogy is the “pound spent day.” We tend not to like units multiplied by time (recall the last time you taught kilowatt-hours?) because rates are more obvious: One metre per second, two chocolate bars per hour, three naps per day, etc. Trying to get the pupils to understand what a “pound spent day” is quickly pushes the analogy out of the easy column. I will return to resistance, at least conceptually, later on in the post, but for now let us agree that it may be a failure of the analogy.

A series circuit with two identical resistors

In this scenario you have moved house to a village that has two whole shops on the same road! If you collect £5 from home, how much money will you spend in the two shops? Of course, the answer is £2.50 per shop and Kirchoff’s second law has yet again been demonstrated. Furthermore, if you leave home to go shopping once per day, you will visit both shops once per day too because they are on the same road and you cannot simply walk past a shop without going in (a rule of the analogy) – current is everywhere the same in a series circuit and Kirchoff’s first law holds true.

A series circuit with two different resistors

This scenario is very similar to the previous one with one key difference: The two resistors have different values to each other. As mentioned above, resistance is a difficult concept to deal with quantitatively in this analogy because of peculiar units unfavoured by pupils. However, at a qualitative level we can make progress. Resistance is given conceptually by how much you like a shop. You find it harder to leave a shop that you love (you feel more resistance to leaving it) and you will spend more money in it.

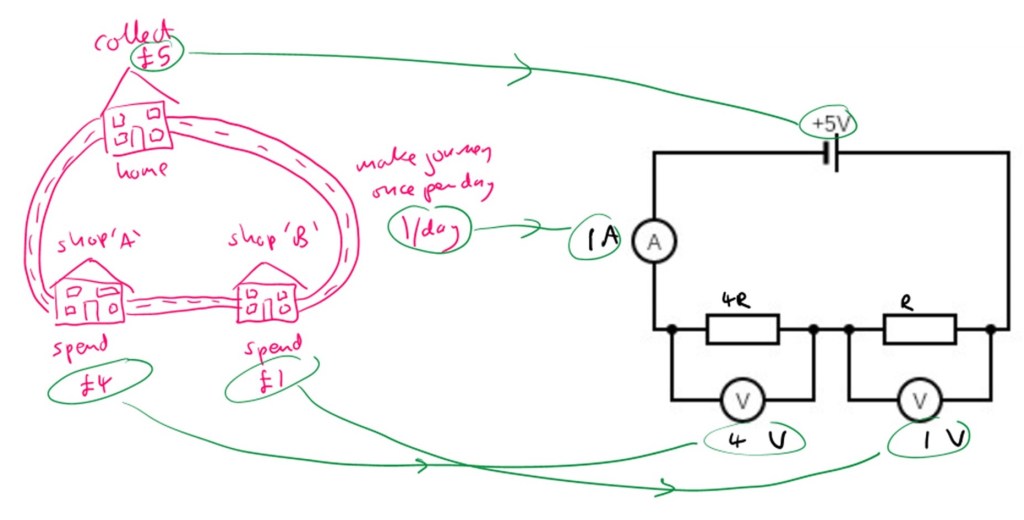

In the example shown below, you prefer shop ‘A’ to shop ‘B’ (by a factor of four…) so you spend four times as much money in shop ‘A’ as compared to shop ‘B’. However, note the two key points:

- You only brought £5 from home to go shopping, so the total amount you spend (shop ‘A’ + shop ‘B’) must equal £5 (Kirchoff’s second law)

- You still visit both shops at the same frequency that you leave home (Kirchoff’s first law)

A parallel circuit with two identical resistors

Now that we have demonstrated the analogy’s power to persuade and explain, we can start to push it further. One of the minimum requirements I would like to see is the explanation of a parallel circuit with two branches and one identical resistor per branch.

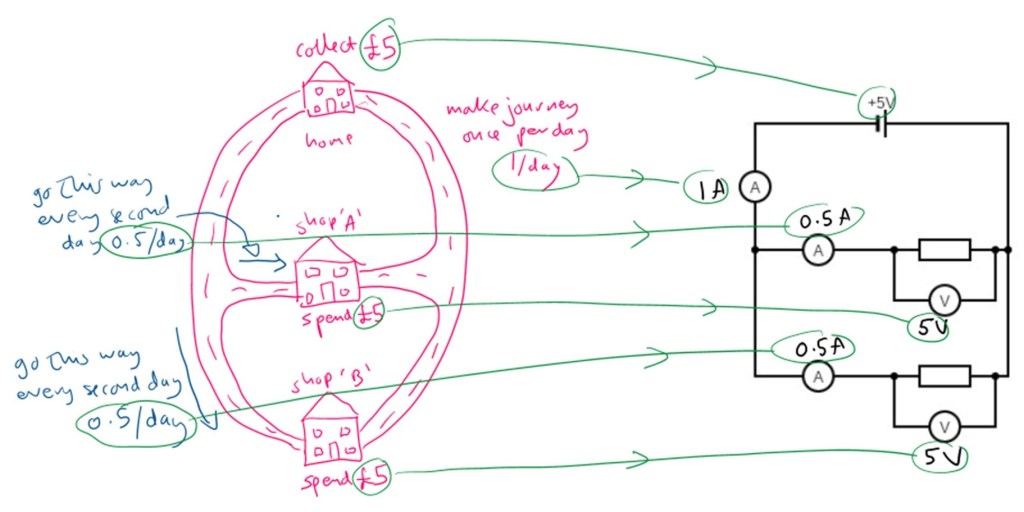

In this scenario, you have moved house to a village that has two roads(!) with a shop on each road. You collect £5 and leave home once per day, but now you have a choice: Do you take the upper road past shop ‘A’ or the lower road past shop ‘B’? As neither shop is your favourite, every second day you take the upper road and every other second day you take the lower road (Kirchoff’s first law demonstrated in a parallel circuit). Furthermore, if you are only going to go past shop ‘A’ and you have £5 in your pocket, you will spend the entirety of £5 in shop ‘A’ (and a similar argument holds for shop ‘B’; Kirchoff’s second law demonstrated in a parallel circuit). Beautifully simplistic!

Semiconductor devices

Can our shopping analogy explain diodes, light-dependent resistors, and thermistors? Let us take a look.

Diodes: In the analogy, if we had a shop with a one-way system or a turnstile, it would not prevent the shopper leaving home and visiting all of the earlier shops on the road. Instead, the diode would be analogous to a one-way system through the town. Easily implementable with the pupils.

Thermistors and LDRs: Ideally, we want a shop that it is easy to leave (and spend less money in) on hot summer days. Sort of like an inverse ice-cream shop. Examples exist, e.g., a hat and scarf shop could represent a thermistor and a torch shop could represent an LDR. However, I find that both of these analogies begin to push the model into the realms of difficulty for the pupils. Instead, talk about inverse ice-cream shops and see what they can come up with.

Keeping track of where the analogy breaks down

Whilst the analogy seems to work well in several scenarios, there are a few areas where it fails:

- Pupils struggle with the quantitative analogy to resistance

- It perpetuates the misconception that a single electron leaves the cell and moves around the circuit back to the cell within a realistic timeframe (not an issue at GCSE level because it is higher order, but a discussion point at A-level!)

- Semiconductor devices require quite some stretch of the imagination and, at this point, it is probably easier to return to hardcore Electricity

Summary

In summary:

- Pupils find Electricity conceptually challenging because we are talking about particles you cannot see and forces you cannot feel

- Analogous circuit models help pupils understand the basics of Electricity

- The models must be easy and comparable

- The pupils can research analogous circuit models as part of their learning

- The shopping model fulfils several requirements with success at GCSE level

With this, I hope I have given you the courage to try out some circuit analogies in your teaching. They are all good up to a point and the pupils can benefit from discussions about where the analogies break down. If you are already using them, which one is your favourite?

Leave a comment