In a recent post about sequencing Electricity at A-Level to go from the microscale to the macroscale, I introduced the idea of using threshold concepts. In that post, I commented that the list of threshold concepts in the literature for Physics is seemingly endless. However, I also pointed out that I think this is an error. I think it confuses subject concepts with threshold concepts. I think there are probably only two threshold concepts in Physics at GCSE but there are many subject concepts.

A subject concept might be that forces come in pairs. For example, Earth is pulling me downwards just as much as I am pulling Earth upwards (the force due to gravity occurs as a pair of forces between the two objects). This is an important subject concept in Physics but it only really applies to forces and it lacks broader application across the specification. There is no lightbulb moment, or perhaps just a flicker.

A threshold concept, on the other hand, is a concept that, once understood, completely transforms one’s perception of the subject. It is a groundbreaking idea that allows bridges to be built across a pupil’s understanding, to increase their chunking of information, and to reduce their cognitive load.

Threshold concepts are probably not exam-worthy, i.e., exam boards do not recognise them in their own right or ask specific questions on them, but I think they help the pupils to learn better and more efficiently.

My first threshold concept in GCSE Physics, and the purpose of this post, is that what we observe on the macroscale is fundamentally due to what is happening on the microscale. An essential point in Physics is that the macroscale is a system of particles, i.e., things on the macroscale are composed of things on the microscale. No complex group theories are required at GCSE (I promise!).

I tend to use the language of particles (i.e., the microscale) throughout my teaching but I only talk about “threshold concepts” per se from Christmas of Year 11 as a way to ease the burden of revision moving through the final topic and into the main exams.

What knowledge do we need from the microscale?

What knowledge is required to make the threshold concept accessible? Quite simply, particles only have two energy stores:

- Particle potential energy. This can be thought of as how close together the particles are. On the macroscale, this is most related to the state of matter that the system is in

- Particle kinetic energy. This can be thought of as how fast the particles are moving. On the macroscale, this is most related to the temperature of the system

Beyond this, we have common sense (and occasionally ions and electrons)!

An example of using the threshold concept: Density

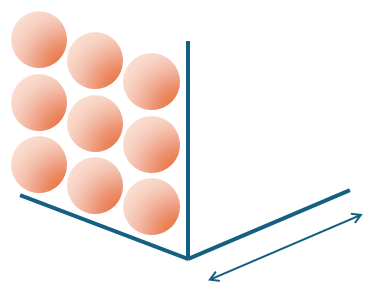

The macroscopic quantity of density tells us by how much the mass of a material has been concentrated within a certain volume. Materials that can pack more mass into a volume have higher densities than materials that can pack less mass into the same volume. On the macroscale, we are dealing with grams or kilograms of material and cubic centimetres or cubic metres of volume. Pupils are expected to know and use the defining equation and should be able to describe experiments to measure the density of a range of different materials. It feels very macroscopic!

However, why do materials have certain densities in the first place? Well, using the microscale, where we consider individual particles, higher density materials are those where the individual particles may have more mass, or their interparticle spacings may be smaller, than the lower density materials. Also, different packing structures (the domain known as “crystallography” in higher education) may be able to fit different numbers of particles into the same space. The macroscopic property of density is very clearly related to the microscale!

Those of you au fait with the periodic table will hopefully know that densities tend to increase as you move down a group. Moving down a group dramatically increases the particle mass at each step for only a small increase in particle size. Thus, density should indeed increase as you move downwards!

We can push the analysis even further. Consider the two types of sweets of the wonderfully spherical maltesers and the twisty turny strawberry whips. It is hopefully clear that maltesers can pack closely together because of their spherical shapes whereas strawberry whips are limited in how close they can be to each other because their long twisty shapes mean that they get in each other’s way. Thinking now about densities of real systems, we can similarly imagine that spherical-ish particles should be able to pack more closely than systems where the particles are long-chain or polymeric. Thus, we anticipate that metals should have much higher densities than, e.g., wood or plastic. This is true! For example, woods and plastics tend to have densities in the 500 – 1,000 kg/m3 range whereas metals tend to have densities in the 2,000 – 25,000 kg/m3 range. The macroscopic property of density does indeed relate to what is happening on the particle scale.

We can push the analysis further still and consider how the density of a material (not water) compares between its solid state and liquid state. The solid state has overall less energy than the liquid state. Of importance, the particles in the solid state have less potential energy than in the liquid state, which means the particles in the solid state are closer together than in the liquid state, thus solids should have larger densities than liquids of the same material. Again (ignoring water), this observation is true: Solids are usually slightly denser than liquids of the same material.

A quick note on water. Water has a special kind of bond called a hydrogen bond. These bonds are prevalent in the liquid state but, in the solid state, they get “frozen out.” So, water molecules in the solid state can be considered as having fewer bonds holding them together as compared to in the liquid state, i.e., water molecules in the solid state sit further apart. This means that the density of ice is less than the density of liquid water (ice cubes float!) and water is the exception to the argument given above. Remember: Never use water as an example when teaching density!

In summary, by remembering that density is fundamentally related to the mass and packing of individual particles, pupils can understand that:

- Systems of more massive particles tend to have larger densities than systems of less massive particles (e.g., moving down a group in the periodic table increases the density)

- Due to packing, on average, the more spherical the particle, the larger the density of a system of them and, conversely, the more long-chain or polymeric the particle, the smaller the density of a system of them (e.g., metals have high densities whereas woods and plastics have low densities)

- For the same particle type, shorter interparticle spacing gives a higher density system (e.g., solids tend to have slightly lower densities than liquids; NOTE: water is the exception)

Furthermore, we have opened the topic to make a very clear bridge to Chemistry and to include higher level engagement by being able to discuss crystallography, cutting edge research, and potential future careers!

Now that we have convinced ourselves of the richness that can be delivered by this first threshold concept, can it be applied elsewhere to demonstrate its ubiquity? In what follows, I suggest just some of the possible applications.

Applying this threshold concept to other areas of Physics

Sound waves

On the macroscale, pupils are expected to know and understand that sound consists of longitudinal waves, the nomenclature associated with these waves, how to use the wave equation, echoes, how to measure the speed of sound in air, and the typical hearing range of humans.

However, sound waves occur due to what’s happening on the microscale. If a solid surface in contact with air pushes against the air, the air particles in the immediate vicinity are pushed closer together, i.e., their interparticle spacing decreases and the air has literally become compressed. If the solid surface then pulls against the air, the air particles in the immediate vicinity are pulled further apart, i.e., their interparticle spacing increases and it is literally rarer to find an air particle in the space (it has become rarefied). So, as the solid surface oscillates/vibrates back and forth, regions of compression and rarefaction are produced in the system of air particles in the immediate vicinity. These regions propagate outwards as they interact with particles further away. This is a sound wave!

Let’s push the analysis.

Firstly, what happens if I remove the air? There will be no air particles to oscillate back and forth so there can be no sound wave. To quote the movie Alien, in space, no-one can hear you scream.

Secondly, is sound faster in air, liquid, or solid? Bearing in mind the vibrations are transmitted between the particles, the closer the particles are to each other, the quicker the particles can interact with each other, and the faster the sound wave should travel. Indeed, sound is fastest in solids, then in liquids, and it’s the slowest in air. You can see this quite easily in the classroom with a micro-timer and a hammer/metal plate. Hit the plate in the air and you will measure a speed of sound of perhaps 340 m/s. However, if you rest the plate on the desktop and then hit it, you will measure a speed of sound of perhaps 1,000 m/s. Sound travelling through the wood of the desk is much faster than sound travelling through the air. Again, returning to TV and the many Westerns that were shown on Sunday mornings in my youth, lying with your ear pressed to the ground should warn of the hundreds of incoming baddies on horseback much quicker than standing upright with hands held to ears.

Heat transport: Convection

On the macroscale, if you heat a fluid, its density decreases, so the upthrust force increases, so the fluid rises. When the fluid is far from the heat source it cools, so its density increases, so the upthrust forces decreases, so it falls. This process repeats in a cycle called a convection current. (You cannot imagine how hard it is for pupils to remember this verbatim for maximum marks in the exam!)

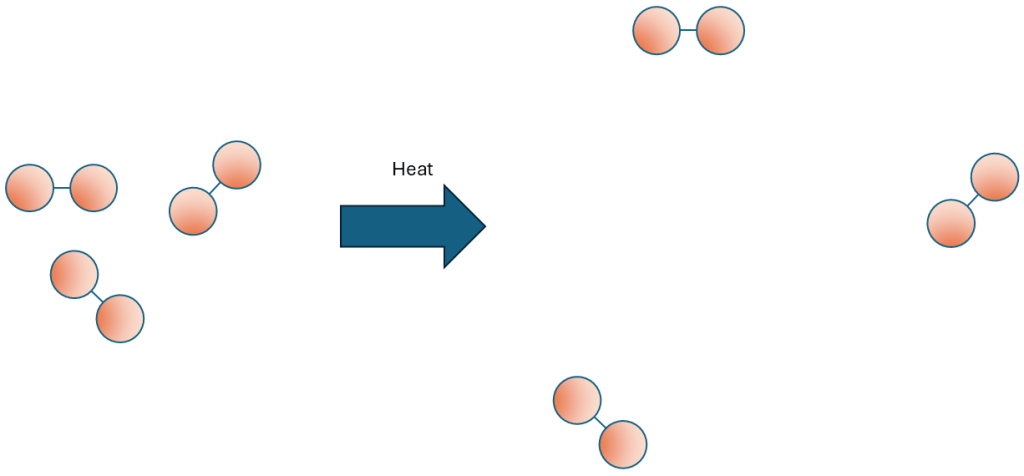

What is happening on the microscale? When you heat a fluid (assuming the fluid stays in a single state) the energy goes into the particles’ kinetic energy stores. This means that the particles are moving faster, which means that they can travel further before they collide with their neighbours (no need to talk about mean free paths unless the class is very much more able!), which means that their interparticle spacing increases, which means that the system of particles now has a lower density than before.

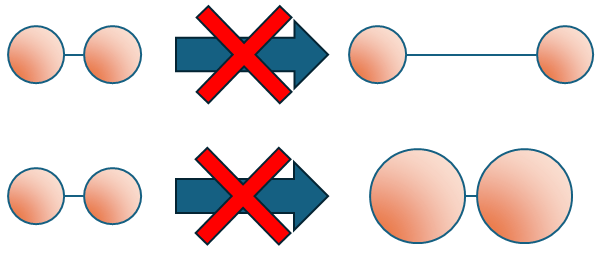

Note that several exam boards are fairly hot on a misconception: It is the system of particles whose density changes and not the individual particles themselves! (An oxygen molecule is always as big as an oxygen molecule, but the space between two oxygen molecules can change).

Electricity

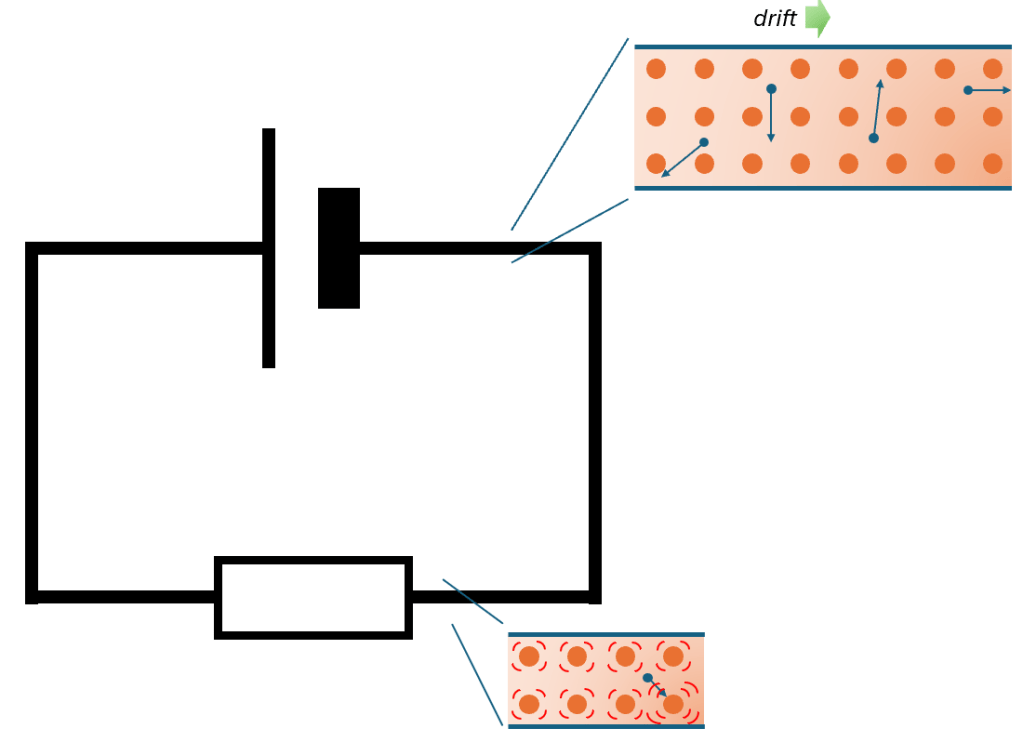

On the macroscale, current flows through a wire because it is being pushed by a voltage. “Resistance” informs us how easy it is for the current to flow.

However, the topic of electricity is clearly dependent on the microscale! We measure current because electrons are moving around a circuit. We measure potential difference because electrons do work on particles as they move around a circuit. We measure resistance because electrons interact with metal ions in a circuit. What we measure, what we observe, is fundamentally due to electrons.

Gas pressure

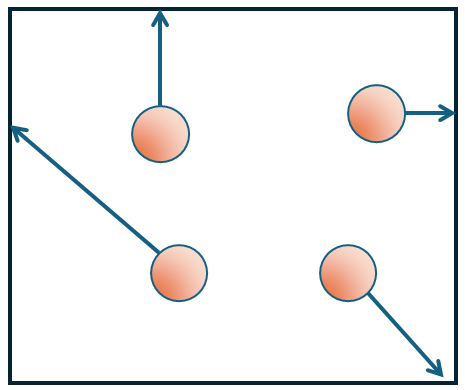

On the macroscale, increasing the temperature or decreasing the volume of a gas leads to an increase in gas pressure (the gas-pressure law and Boyle’s law, respectively). But why is this true? Let’s look at the microscale!

Gas pressure occurs due to gas particles colliding with, and exerting force on, the walls of the container. By increasing the system temperature, the gas particles move faster. This means that they collide with the walls more often and they exert more force with each collision, thus gas pressure increases. Similarly, reducing the volume of the container brings the walls closer together, so, again, the gas particles can collide with the walls more frequently and increase the pressure.

My exam board does not require knowledge of Charles’ law or the effect of the number of gas particles present, but it is hopefully clear how to extend the above arguments for both cases.

Other topics:

We have seen the power of using the microscale across a selection of examples. It can similarly be applied to the following areas of the scheme of work to bring deeper understanding:

- Electrostatics. To explain frictional charging through the behaviour of nuclei and electrons

- Forces: Centre of mass. To describe why we can treat a solid as a point particle in terms of intermolecular forces

- Heat transport: Conduction. To use the language of particles to explain thermal conduction. As an extension, what is the role of dissociated electrons in metals?

- Radioactivity. Rather than simply learning the three types of radiation, to explain what is actually happening in the nucleus in each case

- Solids, liquids, and gases: Heating and cooling curves. To explain the shapes of the curves in terms of particle kinetic energy and particle potential energy

- Space. To describe stellar evolution in terms of a system of humble hydrogen atoms

Again, the range of topics listed above demonstrates the ubiquity of this threshold concept.

Summary

Threshold concepts offer a way to fundamentally transform a pupil’s understanding of a topic. The aim is to reduce cognitive load and to increase chunking by allowing new bridges to be made.

My first threshold concept for GCSE Physics is that what we observe on the macroscale is fundamentally due to what is happening on the microscale. The concept can be used to help explain approximately half of the scheme of work. It allows bridges to be built between topics within Physics. It allows bridges to be built to other subjects (especially Chemistry).

As mentioned at the start of this post, I use the language of particles throughout my teaching, but I do not introduce this collectively as a threshold concept until about Christmas of Year 11. My aim is to give my pupils another way in as they move to revision for the final exams. By introducing the concept at this point, it allows pupils to reduce cognitive load by building bridges. For example, sound travels fast in metals for the same reason metals are good electrical conductors and for the same reason they are good transporters of heat. You only need to learn the Physics once!

I often start by explaining how the taught content is related to the microscale in one example (e.g., density) and I then ask the class to give ideas of where else the threshold concept might be relevant. We build a mind map together and I then split the class into groups to research several of our ideas. We come together later for mini presentations from each group and I then set a homework task to research another couple of the ideas that had not been presented in the lesson.

Leave a comment