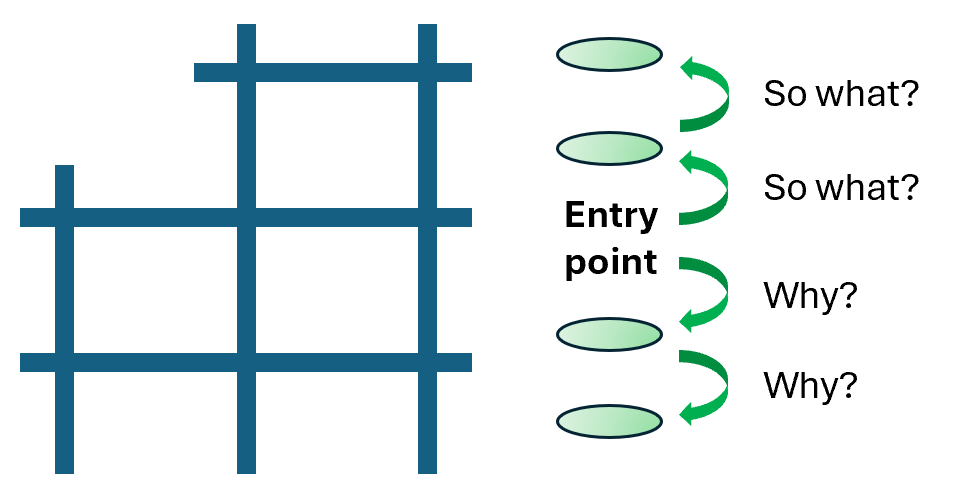

One of the key skills of being a Physicist, or indeed any kind of Scientist, is to question what we see around us. I refer to this with my pupils as the “why” and the “so what.”

The main idea is that if we make an observation, we can further our understanding by looking backwards and asking “why is that true?” or by looking forwards and asking “so what?” Sometimes we may just want to go one way, but on other occasions we may be able to further our understanding by going both ways.

I introduce this line of questioning either in class one-on-one with an individual pupil or by bouncing it around the room from one pupil to another. However, the ultimate goal is for the pupils to internalise this questioning strategy themselves so that they can adopt it in formal assessments. In this respect, it is a key skill to be learned by the pupils. It can be thought of as the ultimate high-level scaffolding in Science!

Here is an example of using “why” in the topic of Electromagnetism. I find that my pupils learn this topic best from a phenomenological viewpoint, i.e., seeing is believing. I usually start the first lesson with the “jumping wire” demo, whereby a wire suspended between the poles of a horseshoe magnet can be made to “jump” from between the poles when a current flows through the wire.

- Why does the wire jump from its original position?

- Because it feels a force

- Why does the wire feel a force?

- Because it is in a magnetic field (misconception)

- Why did the wire not feel a force when no current flowed? (Correction to misconception)

- Because there was no force

- Why do objects feel forces in magnetic fields?

- Because they are magnetic

- So why did the wire feel no force with no current flowing but it felt a force when the current flowed?

- Because the current made the wire magnetic

- In fact, the current created a magnetic field around the wire. Let’s check that with some plotting compasses

You can see how this line of questioning very quickly uncovered a misconception but, more importantly, it allowed the pupils to realise for themselves why the wire jumped. The power of the pupils making this realisation for themselves rather than just being asked to recite a fact from the teacher is immeasurable!

Here is an example of using “so what” in the topic of Space. Space is a beautiful topic because it unites several different fundamental topics within Physics. I love it!

- Hydrogen atoms travelling in space are attracted to each other through the force due to gravity

- So what?

- So they accelerate towards each other

- So what?

- So they collide with each other

- So what? (I usually rub my hands together at this point and mime heating myself by a fire)

- So they heat up

- So what?

- So they start to fuse

- So what?

- So they radiate energy

Again, you can see the power that this line of questioning has. The pupils are able to scaffold themselves to retrieve a solution.

Of course, different pupils will require more or less scaffolding depending on their ability and their level of chunking, so different pupils may give different levels of answer. However, regardless of the level of ability, the Physics is uncovered in a logical way.

Finally, an example using both “why” and “so what” in the topic of Electricity. My pupils find this topic incredibly hard for reasons I have written about in the past and I will undoubtedly return to in the future. I try to ask as many questions as possible in this topic to help scaffold my pupils to a better understanding.

- Why does wire get hot when current flows through it?

- Because the electrons collide with the metal ions

- So what?

- So electrons transfer energy to the metal ions

- So what?

- So the metal ions vibrate more

- Why?

- Because the energy from the electrons was transferred to the kinetic energy stores of the metal ions

- So what?

- The microscopic quantity of particle kinetic energy corresponds to the macroscopic quantity of temperature, so higher particle kinetic energy corresponds to hotter wire

Okay, it is unlikely that any pupil would give all the answers that I just wrote (Electricity is really complex). I would expect a more able group to be able to give all but the final answer and a less able group to give probably only the first two. With this in mind, I would probably use this questioning with some role reversal, i.e., with me asking some questions for the pupils to answer and with the pupils asking other questions for me to answer.

When we are gearing up for exam readiness, my pupils know to self-scaffold in this way for longer answers to questions of the type “describe” or “explain.” In particular, they know to find at least one bullet point more than the number of marks awarded (e.g., find six bullet points for a five-mark question). Also, I love to stress the point to my pupils that Physics is not English! Bullet points are fine rather than paragraphs and you can number the bullets after you have written them, so the order that you originally put them on the page does not matter either.

I think the beauty of this type of scaffolding is that it is wonderfully simplistic (the pupils can remember it in the exam), it is open-ended (there are multiple right answers, so it is easier to experience success), it slows the pupils down (they give more attention to descriptive answers), they can practise it at ease with each other or on their own, and they can enter into a description at any point because the questioning necessarily allows to look both forwards and back. Furthermore, it can be extended to other subjects directly.

Leave a comment