This post is about OCR Physics-A at A-Level, specifically Chapters 8-10 of “the textbook,” which are about Electricity. In fact, this post is not about the textbook, it is about Electricity, or indeed Physics, in general; the textbook just provides a focus.

At several schools where I have taught, the schemes of work have followed the textbook verbatim.

The textbook is a great book, introducing the concepts well and providing questions every couple of pages or so for the pupils to test themselves. I like it a lot. However, Year 12 pupils that I have taught tend to struggle with Electricity, often scoring 10-15% lower on this topic than on other parts of the course. After a lot of reflection, analysing data, interrogating the pupils, and discussing with my co-teachers, I think the reason is that the order of concepts in the textbook does not suit my pupils well. Do not get me wrong, the textbook is great, but the choice to map a scheme of work to it directly is nonideal. (Note that I am only referring to Chapters 8-10 and not later chapters on capacitance or electric fields, which I think must necessarily come later due to their increased complexity).

My pupils struggle with the fact that the material jumps back and forth between what is happening on the microscale and what is happening on the macroscale. It takes a lot of cognitive load to keep track of the scale we are dealing with and how it relates to what we were describing half an hour earlier on the other scale. Furthermore, the microscale is very difficult because we cannot see it or feel it, so it needs more attention than an occasional drop-in. Switching back and forth and not giving the microscale the respect it demands saps the cognitive load of the pupils and they have nothing left to learn with.

If our current scheme of work is suboptimal, what can we do to change it?

A new way of thinking

It has become more and more popular in recent years to model schemes of work on the “big ideas” of the subject. Unfortunately, in Physics, “electricity” is usually listed as one of the big ideas without breaking it down further in any meaningful way, i.e., using big ideas may help us map the entire scheme of work but would not necessarily help us make the content within the topic of electricity any easier. Instead, my proposal is to use “threshold concepts.”

A threshold concept is a concept that, once understood, completely transforms one’s perception of the subject. For example, in Mathematics a threshold concept at junior school might be that you do not need to count real oranges because pictures of oranges or even symbols that represent numbers alone yield the same result (thus, the real-pictorial-abstract method of teaching Mathematics is born).

Many authors have written about threshold concepts in Physics, and, with each new contribution, the list of threshold concepts seemingly increases. I think this is a mistake. In fact, I believe that there are probably only two real threshold concepts in Physics at GCSE and a further one at A-Level (I shall write another post on this soon). For me, one of the two key threshold concepts in GCSE Physics is that what we observe on the macroscale is fundamentally due to what is happening on the microscale. Broadly speaking, what this means is that systems of particles do things because the particles themselves are doing things.

Back to electricity and what our new approach means… We measure current because electrons are moving around a circuit. We measure potential difference because electrons do work on particles as they move around a circuit. We measure resistance because electrons interact with metal ions in a circuit. What we measure, what we observe, is fundamentally due to electrons.

Using the new way

Using my threshold concept to redefine the topic of electricity in OCR Physics-A at A-Level means that there are two clear sub-topics: 1. The microscale (what I call “Electrons”) and 2. the macroscale (what I call “Circuits”). Previously, the topic had three chapters, thus three sub-topics, in our scheme of work, so I have reduced it by one.

The microscale (“Electrons”)

Here are what I think are the fundamentally important points for teaching electrons on the microscale in Year 12. Each point is worth at least one lesson (I actually take five lessons for the four points given below):

- Electrons are charge carriers

- Electrons have a finite and precise charge – smaller charges do not exist and larger charges are integer multiples of this precise charge

- The electron charge is very small and is impractical for most desktop experiments, so we use the SI unit of coulomb to refer to easily measurable charges

- Charge is conserved, so if ten electrons flow into a piece of wire, ten electrons had better flow out (Kirchhoff’s first law)

- Net flow of electrons is called “current”

- How electrons move

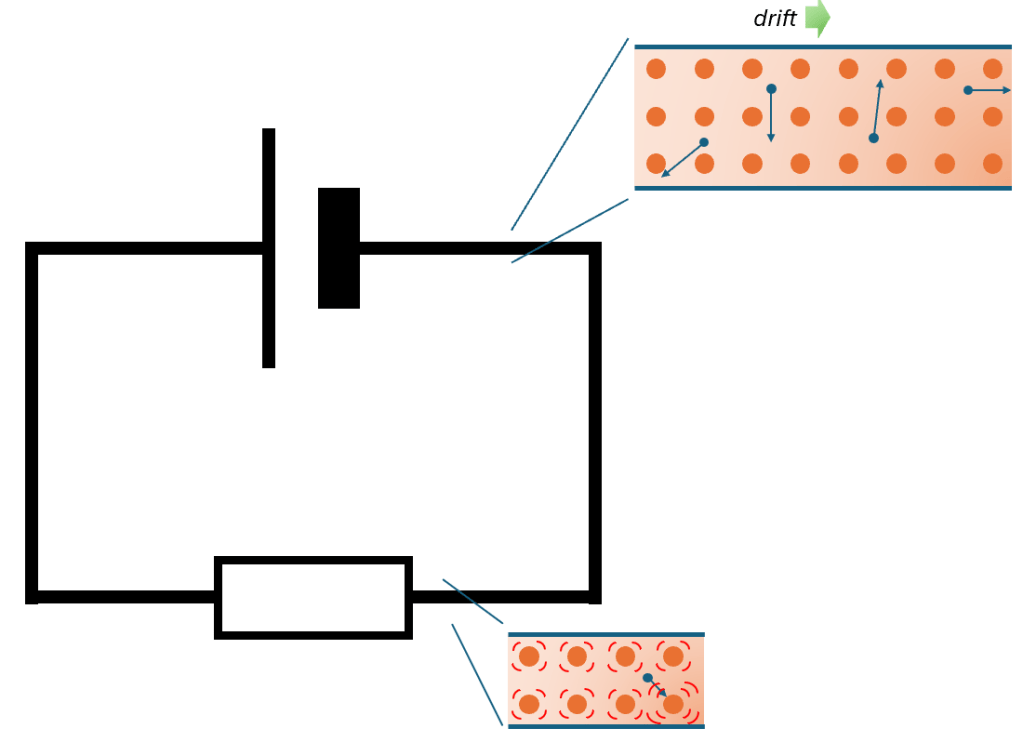

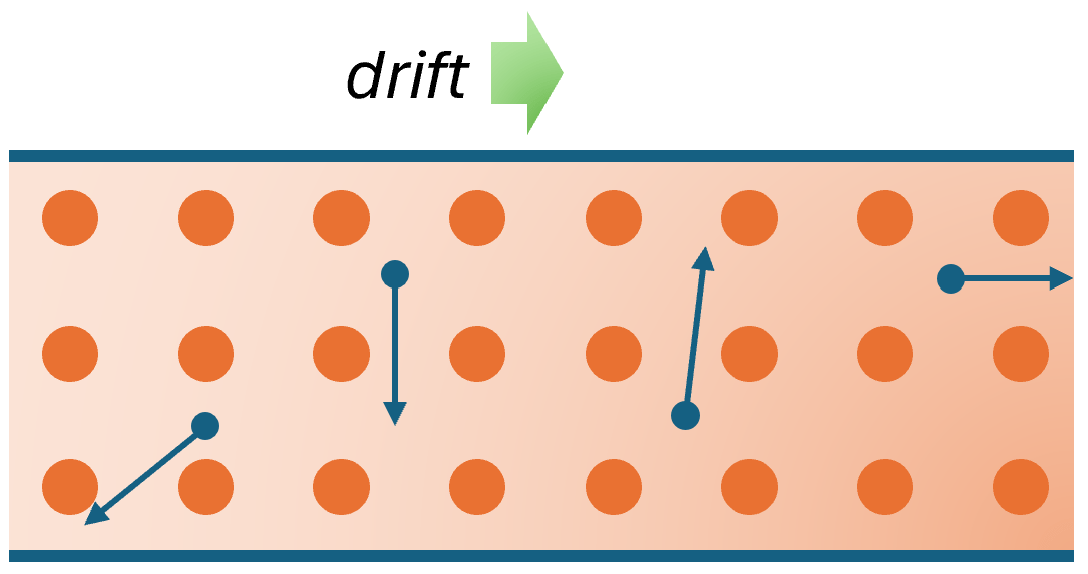

- At zero voltage, at room temperature, electrons can move very fast (e.g., thousands of metres per second), but they are moving in random directions so their overall net motion (the current) is zero

- At finite voltage, the electrons still move incredibly fast, but now their motion is no longer random because, on average, more electrons are whizzing along in one direction than in the other. The centre of mass of a selection of electrons drifts (very) slowly from the negative electrode to the positive one. When I say “slowly,” it might be the width of a human hair per second. This net drift of electrons gives us a non-zero current

- The electrons drift around a circuit because they are trying to minimise their energy, so they drift away from the negative electrode and towards the positive one

- The drift velocity depends on how many electrons are available, which changes by many orders of magnitude depending on whether the material is an insulator, semiconductor, or conductor

- Electrons as transferrers of energy

- Electrons can transfer energy to particles in circuit elements

- Electrons can receive energy from particles in circuit elements

- The amount of energy transferred per electron is vanishingly small, so it is more practical to refer to the amount of energy transferred per coulomb of electrons (and this is given the name of volt)

- The energy transferred to a coulomb of electrons is given the special name of electromotive force (which is not a force)

- The energy transferred from a coulomb of electrons is given the special name of potential difference

- Due to the law of conservation of energy, electrons can only transfer out as much energy as they initially took in. This means that electromotive force must equal potential difference in a loop of an electrical circuit (Kirchhoff’s second law)

- Resisting electron flow

- As electrons move through a material (e.g., a copper wire) they are attracted to the positively charged copper ions. This means they can interact with the copper ions and transfer energy to them

- The more energy the copper ions accept, the more they vibrate about their fixed positions, so the more they obstruct the electrons (the energy the ions accepted went into their kinetic energy stores)

- The obstruction of electron flow is referred to as resistance. Short paths are less resistive than long paths, wide paths are less resistive than narrow paths, and conducting paths are less resistive than semiconducting paths, which are less resistive than insulating paths

- Particle vibrations on the microscale correspond to temperature on the macroscale, so the resistance to electron flow leads to heating, known as resistive heating

- As the electrons drift around a wire, increasing the obstruction to the electrons (i.e., increasing the resistance) slows the electrons’ drift (i.e., current) down (Ohm’s law)

The macroscale (“Circuits”)

And here is how I think the macroscale can be taught (I take seven lessons to teach the five points):

- Basics of circuit analysis

- Circuits can be represented as circuit diagrams

- Currents at a junction are conserved (Kirchhoff’s first law)

- EMF is equal to PD around a closed loop (Kirchhoff’s second law)

- Circuit analysis can be completed by sequentially applying Kirchhoff’s first law, then Kirchhoff’s second law, then Ohm’s law

- As a result of the previous point, resistances add up in different ways depending on whether they are in series or in parallel. (It is always worthwhile deriving the resistor addition rules at A-level)

- IV characteristics

- Different circuit elements have distinct IV characteristics

- A resistor’s characteristic is one of direct proportionality between I and V, with a higher resistance having a shallower slope

- A lamp’s characteristic is an “s” curve. I and V are almost directly proportional through the origin but, as the current increases, resistive heating increases (so it emits light!) and the resistance increases

- A diode’s IV characteristic is zero for all negative polarity potential differences, right up to a positive threshold voltage. Beyond this, the current rapidly increases as more and more electrons become available to flow

- Real systems

- Real power supplies have internal resistance, so the energy per charge at the terminals is less than the energy per charge provided by the supply (the electrons do work in moving from their point of origin to the point where we attach the leads)

- Circuits as sensors

- Diodes, light-dependent resistors, and thermistors are all semiconductor devices

- Semiconductor devices have the special property that the number of electrons available to flow as current increases dramatically with energy input

- A potential divider circuit is a special circuit that can be used for sensing

- With the correct positioning of semiconductor devices in a potential divider circuit, you can create circuits that, e.g., switch on air conditioning when it gets hot, switch on heaters when it gets cold, regulate oven temperature, switch on lights when it gets dark, etc

- Electrical power

- Energy transferred per unit time is called power

- Real people have to pay for electricity in their home and a useful unit for energy on the home-scale is the kilowatt-hour

If you want to see the above broken down into the OCR’s specification bullet points:

- Click here for my lesson overview for Electrons

- Click here for my tick list for Electrons

- Click here for my lesson overview for Circuits

- Click here for my tick list for Circuits

Final thoughts

So, there you have it. A different approach to teaching electricity in year 12 of OCR Physics-A. From a “flow of concepts” standpoint, it is absolutely more beautiful and logical than following the textbook verbatim through chapters 8 to 10. In fact, understanding the microscale is key to understanding the macroscale in many different areas of Physics and, if you are brave enough to roll out a similar method of teaching GCSE, your pupils will be ready and waiting by the time you embrace the methodology at A-Level! I guess the question you need to ask yourself is “why am I doing what I am doing?” If the answer is to create Physicists, try the micro/macro approach.

Leave a comment