Space is probably my favourite topic in all of Physics. It can be taught as a standalone unit, but I think this undersells the beauty of the subject. Instead, I like to teach Space by drawing together several different aspects of previously taught Physics, requiring the pupils to build bridges between seemingly disparate islands of knowledge.

My method may appear at first glance to add unnecessary complexity – pupils might have been weak on earlier topics, or perhaps they are unfamiliar with this style of logical reasoning. However, I think this impression is incorrect; there are really meaningful gains to be made by persevering. It reinforces the topics where the pupils were weak and it helps them form connections and build resilience to ease cognitive load.

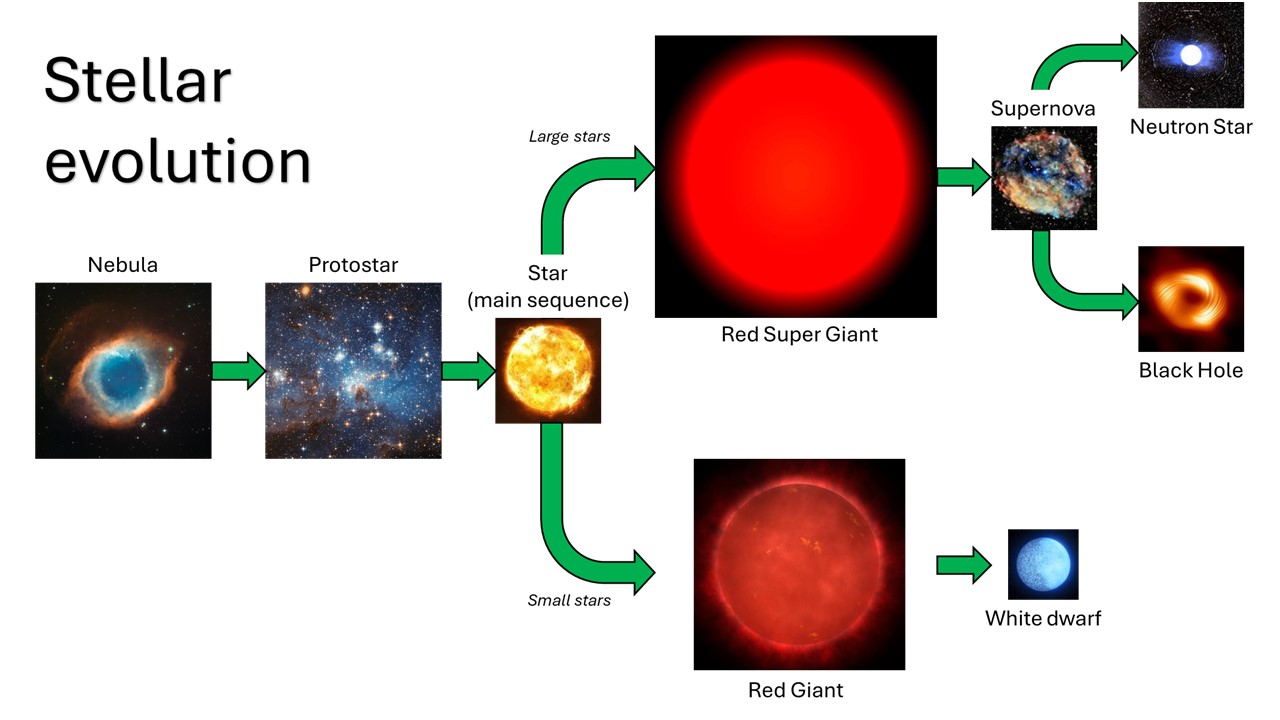

It begins with stellar evolution. How are stars born? How do they die? And what happens in between? All good Physicists have a poster for this, like the one here.

My preferred method of teaching is via Socrative debate. I have a conversation with the pupils where my job is to steer, scaffold, and support them, as they reason themselves to the answers.

The route to Main Sequence

Our story starts with two humble hydrogen atoms journeying through space. Hydrogen is the most basic element there is. Its atoms are uncharged. They are abundant. They are incredibly light. Hang on… I have just mentioned something really special about them… they have mass!

So, two massive hydrogen atoms are journeying through space. Wasn’t there a force we learned about that affects things with mass? (At this point, it is important to take an aside. I personally think “weight” refers to the force of a low mass object with respect to a high mass object. Perhaps I mean when one object is light enough for the field of the larger object to appear uniform. In any case, I do not like using the word “weight” when talking about stellar objects. So too, I think “gravity” refers (at best) to an energy, not a force. For the purposes of stellar evolution, I will settle for “the force due to gravity.”)

Okay, two massive hydrogen atoms are journeying through space and they are attracted to each other through the force due to gravity, so what do they do? They move towards each other. Physics is easy!

So what?

Well, the two hydrogen atoms are now closer together than before, so the magnitude of the force due to gravity is larger than before, so they move together even more than they did last time. Bearing in mind the force due to gravity is the only force they are experiencing, it is unbalanced and the hydrogen atoms accelerate towards each other (this one sentence sums up all three of Newton’s laws… build those connections!).

Of course, in the explanation given here I am talking about two hydrogen atoms for ease, but, in reality, there could be billions and billions of them. All of these gas atoms coming together to form a cloud, which we call a Nebula.

Eventually the hydrogen atoms are going to do what? Two objects accelerating towards each other will eventually…. collide. Okay, this is a borrowed word from English because it is impossible to define a collision on the atomic scale, but “collide” is acceptable for every exam board.

Time to perform. Clap your hands together and rub. What happens when objects collide? Mime heating your hands on a fire. They warm up! Gravitational potential energy was transferred to kinetic energy and now to thermal energy (connect, connect, connect).

Things that are hot glow. Think about the young blacksmith, heating her iron in the furnace. It glows red, then white, then blue as it gets hotter. The gas cloud starts heating up so it begins to glow and it is now called a Protostar.

Quick. Dive into solids, liquids, and gases. If a system gets hotter its particles move faster.

Didn’t we learn something in nuclear physics about particles moving very fast? Their nuclei can overcome electrostatic repulsion and they can fuse together, forming larger particles and radiating energy. So, two hydrogens can fuse together. A simple calculation on the whiteboard from a randomly selected pupil will show that they fuse to form… helium (no need to go into stellar nucleosynthesis equations unless you are feeling hardcore). If it is fusing, it is a star. If it is fusing hydrogen to helium, it is a Main Sequence Star.

Alright, we have this nuclear explosion radiating energy outwards. If we want to step up to A-Level to entice the class, we can talk about how electromagnetic radiation is able to transfer momentum to matter. Otherwise, we can gloss over all of that and simply say that the explosion creates a force with its very own special name of “radiation pressure.”

We are moving into familiar ground. There are now two forces: The force due to gravity is pulling matter inwards and radiation pressure is pushing matter outwards. An equilibrium between the two forces is formed which dictates the size of the star.

To the best of our knowledge, all stars undergo the preceding path to Main Sequence; it is (quite literally) universal. Is there any new Physics in it, or are we just combining old ideas? Difficult to say. But we have definitely started combining previous ideas into one larger picture.

What happens next depends on the size of the star.

Little stars like our Sun

The force due to gravity is pulling matter inwards. The radiation pressure from fusion is pushing matter outwards. The star is fusing hydrogen into helium. Eventually, the star will run out of fuel, just like a car running out of petrol. What is its fuel? Hydrogen! What happens if it runs out of hydrogen? It stops fusing! What happens if it stops fusing? Radiation pressure stops! What happens if radiation pressure stops? The forces are unbalanced and only the force due to gravity remains. So what? The star collapses!

All of the atoms are pulled inwards because of the force due to gravity. We follow the same storyline as before as they get faster and faster and they collide and the system heats up. This time, they are much faster than before so they can fuse more. The system can fuse hotter. It can fuse larger elements to form even larger ones. All atoms up to about carbon on the periodic table.

Fusion has reignited; we have regained radiation pressure. Two competing forces; the star expands to its equilibrium size. Fusion is hotter than before; the radiation pressure is larger than before. The star is much bigger; it is a Red Giant.

At this point, the pupils begin to notice a recurring theme… We will eventually run out of fuel (again). Fusion will stop (again). The force due to gravity will lead to system collapse (again). BUT, this time there is insufficient energy to fuse even larger elements, so the system collapses smaller and smaller. It doesn’t shrink down to nothing because of something called electron degeneracy pressure (university-level – you cannot have too many similar electrons in the same system), so it shrinks down to a finite size where this electron degeneracy pressure is in equilibrium with the force due to gravity.

It’s not fusing, so it’s not a star. It’s dead. It’s a dead, hot, ball of gas. Almost as massive as the Sun. Hotter than the Sun. Roughly as big as Earth. It has oodles of thermal energy that will radiate out into space over the next few billion years. It’s a White Dwarf. A dead White Dwarf.

From two humble hydrogen atoms, through the creation of a star, to the formation of lower elements on the periodic table, to a dead White Dwarf. What a journey!

When the energy has dissipated, it will cease radiating, and it will become a Black Dwarf. Equally dead but no longer radiating.

By now, the pupils have given loads of great answers in the discussion. Let’s give them a short assessment. Can they match the first five stages of evolution to their correct descriptions in this worksheet?

Big stars (maybe 8 times the mass of the Sun or larger)

Big stars behave somewhat like little ones straight after Main Sequence. They go through the same cessation of fusion, collapse, reignition, expansion… BUT, this time their additional mass gives sufficient energy on collapse to allow fusion of all elements up to iron on the periodic table once they reignite. More energy means more radiation pressure, which means the equilibrium between radiation pressure and the force due to gravity occurs at a larger size than before. Not a Red Giant, but a Red Super Giant! (Astrophysicists were beaten only by Particle Physicists when it came to naming things).

We have iron on Earth. This may have come from the remnants of a Red Super Giant. (However, wait for a couple of paragraphs and it gets even more exciting…).

Similar to a Red Giant, a Red Super Giant will eventually run out of fuel and collapse, unable to reignite to form an equilibrium. This time, the added mass makes the collapse catastrophic. All of those particles from all of those elements getting pulled into a central point because of the force due to gravity. There is only one possible outcome. A mighty nuclear explosion. “Pop.”

The star blows up with so much force that a lot of the matter is blown out into space to form Nebulae elsewhere. The amount of energy involved is so large that all known elements are formed during this explosion (excluding the weird ones at the end of the periodic table that only exist for fractions of seconds in labs on Earth). We have heavy elements on Earth! We dig them out of the ground! This means that Earth must have been formed from the remnants of such an explosion. The explosion is so large that it has its own special name: A Supernova.

Earth, our home, exists because two humble hydrogen atoms, a long time ago, came together with a lot of their friends and it all went catastrophically pop. Gravity, eh, not bad!

Is this the end of the story? Almost. For sure, the entity is no longer fusing. For sure, it is dead. But, there are two possible deaths depending on whether or not the core of the Red Super Giant survives the Supernova.

On the one hand, if the core does survive, we end up with a Neutron Star (it’s not fusing, it’s not a star, don’t ask). These are so called because they are made of neutrons and this is because their internal pressures are sufficiently large that protons and electrons combine to create neutrons. In fact, these stars are slightly more massive than the Sun, but they are only a few kilometres wide. That’s really dense. Why don’t they collapse? Because there is another new force (university level, again) called neutron degeneracy pressure (you cannot have too many similar neutrons in the same system), which forms a stable equilibrium against the force due to gravity.

On the other hand, if the core does not survive, the system collapses into something so dense that not even light can escape. A Black Hole.

Time to finish the worksheet from before.

What’s new?

That was stellar evolution for GCSE. But, was there any new Physics?

If you teach Space at the end of the course, which is a fairly common way to plan a scheme of work, we already knew:

- Hydrogen atoms

- The force due to gravity

- Unbalanced forces

- Acceleration

- Collisions

- Heating

- Gravitational potential energy

- Kinetic energy

- Thermal energy

- Particle speed

- Electrostatic repulsion

- Fusion

- Stable equilibria

- Periodic table

- Radiation

- Dissipation

- Density

And the following bits were new to us:

- Radiation pressure (do not need the Physics, just the name)

- The fact that protons and electrons can combine to form neutrons (do not need the Physics or the name)

- Electron degeneracy pressure (do not need the Physics or the name)

- Neutron degeneracy pressure (do not need the Physics or the name)

- Names of the stages: Nebula, Protostar, Star (Main Sequence), Red Giant, White Dwarf, Red Super Giant, Supernova, Neutron Star, and Black Hole (just need the names)

So, for GCSE, all examinable Physics was already known. All we have done is added some new keywords to our glossaries. When teaching Space, we are essentially revising earlier topics and tying together many different ideas into one whole. It’s beautiful!

Is that it?

Now that the stages of evolution are known, along with the physical processes involved, our job is done. However, stopping at this stage misses a great opportunity to tie even more previously taught material in. I like to add two extra stages.

Firstly, bearing in mind the number of times in the description above we were talking about energy, this sheet can be used to assess understanding of parts of stellar evolution in terms of energy stores and transfers.

Next, this sheet allows us to assess stellar evolution in terms of forces.

Finally, the lesson is almost at an end and we have assessed physical processes, energy stores and transfers, and forces, so let’s wind it all up with this exit ticket to formatively assess the pupils’ progress and to inform our starter exercise next lesson.

Summary

If Space is the final topic in the scheme of work, it can (and I believe should) be used to bring together several ideas from previously taught material into one coherent whole. It unifies Physics. It demonstrates the beauty of the subject. It reinforces past knowledge. It builds connections. It strengthens resilience.

Space usually begins with Stellar Evolution. There is essentially no new Physics in this. Don’t ask the pupils to learn it by rote. Use it to excite and motivate. Don’t waste the opportunity!

Listing all resources in one place:

wow!! 49A one-off lesson on data digitisation

LikeLike